American Gothic #2: American Gothic Fiction

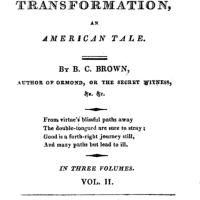

The first manifestation of the Gothic impulse in America was naturally felt in literature, as the Gothic Fiction of England and Europe made its way to the United States in the second half of the 18th Century. Curiously the first important work of American fiction, Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland, published in 1798, was also not only a Gothic work, but upon retrospection it was also clearly the first example of the American Gothic idea. (For questions of definition please refer back to American Gothic #1.)

In Wieland we find many of the hallmarks of the American Gothic outlook. There is a sense of darkness at the edge of the frontier, of fanatical quasi-Christian religious cults leading to ritual murders and strange motifs like ventriloquism (foreshadowing the spiritualism scams commencing another fifty years down the line). In his book Ormond (1799) Brown describes the nearly post-apocalyptic scenario of a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia. In Arthur Mervyn (1799) he describes Cormac McCarthy-like violent upheavals on the Pennsylvania frontier. (Or perhaps we should say that McCarthy writes in Charles Brockden Brown-like spasms of frontier violence.) In Edgar Huntley (1799) sleepwalking is a major component to the tale. In his forward to that book Brown relates his purposeful decision to abandon the castles and manner houses of the European Gothic Fiction and to fully Americanize his novels by including American themes because; “The incidents of Indian hostility, and the perils of the western wilderness, are far more suitable; and, for a native of America to overlook these, would admit of no apology. These, therefore, are, in part, the ingredients of this tale, and these he has been ambitious of depicting in vivid and faithful colours.”

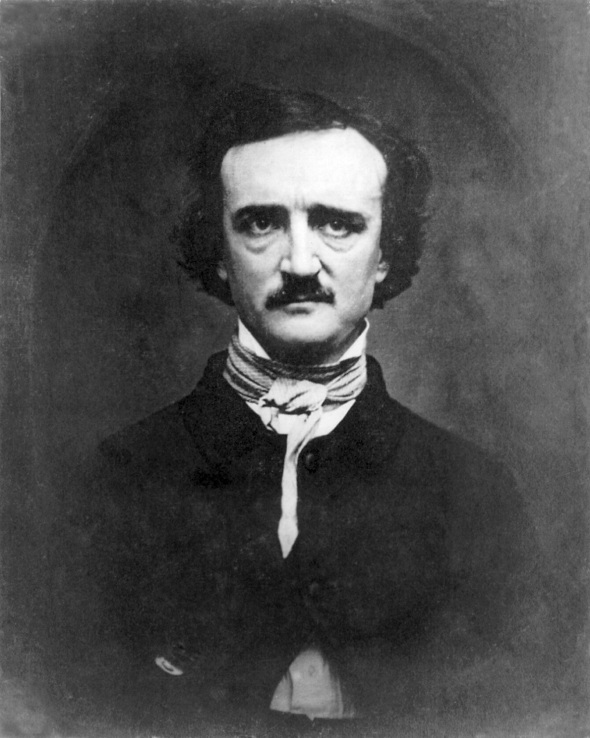

And those colours, the colors of American Gothic literature are overwhelmingly autumnal. All American Gothic culture seems tinted by the dank browns of barren trees and wood planked ghost towns, the cracking white paint of old southern mansions and Texas Chainsaw white picket fences, the rotting mold green of decay, the oranges of dead leaves and collapsing pumpkins and above all the grays of thick leaden skies. It is impossible to imagine the American Gothic vision to contain the greens of spring, the yellows of summer or the blues of sky and reflective waters, unless they can be tainted. And the master of American tainting is Edgar Allan Poe.

Poe was certainly influenced by Brown, as were Washington Irving and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Poe’s works certainly still often hearken back to old Europe. Yet in many ways Poe lays the foundation for what will be the American Gothic tradition. The narrator is often completely unreliable and much great American Gothic Fiction has followed this path. (See Ambrose Bierce.) (See HP Lovecraft.) (See Shirley Jackson.) (See Jim Thompson.) There is more than a trace of psychological instability. (See reams of American fiction at this point.) Brown was also deeply concerned with contemporary psychological issues and fads. Poe uses hypnotism. Poe invents so many new tropes that entire genres kick into gear by the time he is done: Not only horror, but his tales of “ratiocination” or what we now know as the Detective Story or the Mystery. And that leads to questions about the relationship between the Gothic tale and the Mystery. And that also helps to understand how Hardboiled Detective literature and Film Noir seem so aligned with the American Gothic mode.

Poe is obviously a lengthy subject and we are only skimming the pond here. But as long as I am in the 19th Century I must mention Ambrose Bierce, who is as sarcastic and cynical as Mark Twain, yet darker than Poe, perhaps the blackest purely American vision ever committed to paper. His Devil’s Dictionary is a uniquely sardonic concoction. His odd and humorous short stories delineate the motifs of comic aspects of American Gothic, preparing the way eventually for the likes of Holden Caulfield and the grave puns of EC Comics. He begins An Imperfect Conflagration with a memorably mordant sentence; “Early one morning in 1872 I murdered my father – an act which made a deep impression upon me at the time.” Stories like Oil of Dog and The Hypnotist are bleak comic gems. But it was in his Civil War stories that “Bitter Bierce” turns on his full power. As the only important fiction writer to actually fight in and write about the war, his works are a crucial testament to the stark horror of those Civil War battlegrounds. Nothing so bleak has ever been penned. An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge is justly famous for its last moments of false hope before the snap of an executioner’s rope. And Chickamauga is told in such a way that the final revelation as seen through deaf mute child’s eyes can simply eviscerate the modern reader who is used to at least at shard of ambiguous hope. Bierce died as he lived and wrote, as if he were a wanderer from McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, disappearing somewhere in the Mexican dessert searching for death before a firing squad.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890 – 1937) Depicted by Pulp Artist Virgil Finlay in His Imaginary 18th Century

The next really important stop along the way is HP Lovecraft. His work is often Gothic after the European model, or even Science Fiction and Fantasy. But there is a core of his work that mines the putrid vegetal remains of New England for its Gothic terror. Shadow Over Innsmouth, The Dunwich Horror, Cool Air and Dreams of the Witch House, among other stories, portray a New England soaking in hidden secrets. The lineage that runs from Cotton Mather, through Nathaniel Hawthorne, Lovecraft, Tom Tryon, and even Stephen King, spells out many of the aspects of New England Gothic. The fact that these areas were settled early adds to the availability of lost and haunted imagery ripe for use.

And the same is obviously true for the South. But the American South also has one additional feature that is crucial to its Southern Gothic literature. It is its complete defeat during the Civil War. It is not merely the broken houses and burnt over lands, it is in its crushed people that the Southern Gothic writer finds so much inspiration. Boo Radley from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird comes to mind. The kinds of characters who people William Faulkner’s novels or Flannery O’Connor’s short works are a very different species from even the Gothic writers from other parts of the country. They are broken or deluded, cursed and noble, visionary and confined. Again we approach a vast subject for study here. But the important point is that Southern Gothic ultimately is species of American Gothic.

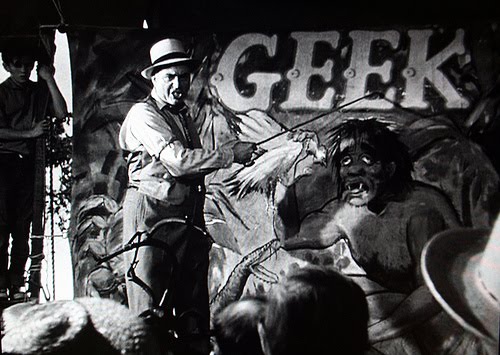

And there are so many other important American Gothic works: Shirley Jackson’s horror stories are as subtle as wilted corsages. Richard Matheson has often mined the American Gothic quarry. Likewise Consider Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked this Way Comes. Images of the dark traveling carnival take on American Gothic hues instantly. The now forgotten works of William Lindsay Gresham infest the mind at this point, particularly his non-fiction study of carnies from the inside out called Monster Midway and his classic Nightmare Alley, which really blends Hardboiled fiction completely with the Gothic, and specializes in mentalist scams and cold reading and other aspects of carnival chicanery. (Not to mention his revelation of the sinister aspects of a being called the Geek.) And of course there is Cormac McCarthy who is the reigning master of the Southwestern branch of American Gothic, and a good bet for consideration as America’s preeminent living novelist.

Gresham Introduced The Geek to Popular Culture. This Geek was Not the Obsessive and Pitiful Character of the Early 21st Century. The Carnival Geek was the Human Being in the Most Lost Degraded Sub-Animal Form – Pure American Gothic in the Deepest Sense.

And finally I will mention what might be the ultimate American Gothic novel ever written: that quest for the white whale aboard the now ghostly remains of the whaling trade – Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

Is it starting to become clear yet, the shape of this American Gothic creature? If so stick around as we examine the other American Gothic modes.

Coming up next: American Gothic in the visual arts.

Byrne Power

Haines, Alaska

5/18/11