American Gothic #1: What is American Gothic?

The terms Goth and Gothic have been apply to numerous phenomena: the Germanic tribe that sacked Rome, the cathedrals of Medieval Europe, horror and supernatural literature in the early Romantic age, romance novels of a certain style, the writings of American southerners William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor and more recently to the music and lifestyles of those attracted to images and particularly music of death and darkness often with a Victorian twist. And while these arts and artists appear to be only obliquely related there is indeed a stream that runs through them all. It is felt but rarely articulated.

The Goths were among the many tribes at Rome’s frontiers. Seeking sanctuary within the Empire, the Huns closing in from the hinterlands, they were allowed to settle in Dacia, present day Romania. The Goths only partially acclimatized themselves to life in the decaying pax romana. But Roman arrogance and misrule eventually led them to revolt. They sacked Rome and were given kingdoms of their own in Italy and France. Eventually the fracturing Rome of the Caesar’s became more and more of a memory. The Goth’s had envied Rome though, even as they were allowing the last dregs of its essence to slip through their feudal fingers. The new Gothic and Germanic Europe began to forget and to forget deeply. Among the things forgotten: architecture, engineering, crop rotation and ultimately the Goths themselves. But one can imagine the children of these Ostrogoths and Visigoths, these warlords, riding through the slowly crumbling ruins of temples and aqueducts and amphitheatres longing for the Rome that created them.

Eventually the ancestors of these feudal rulers did create their own art and architecture. They created cathedrals that pierced the clouds, covered in images of Christian saints and demonic gargoyles. And even later in the self-proclaimed Renaissance, the very word proudly meaning ‘new birth’, the cathedrals of this earlier era were called ‘Gothic’ as a term of derision, a term related to those barbarian hordes who thought they could rule the great Roman Empire. The post-Roman age then became known as the ‘Dark Ages’.

In mid-Eighteenth Century German and English Romantics, in their flight from the excesses of voltairian reason, rediscovered the Middle Ages. They considered Gothic cathedrals and the detritus of ancient Europa the perfect fodder for the Romantic Soul. And they began to write. Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis all wrote of old abandoned mansions, dark and stormy nights, chains rattling in the basements, unspeakable family secrets, terrible things too awful to describe and ghosts. Again the longing for something old crept into the proceedings. The word Gothic now seems to have taken on its dreadful quality.

The Gothic idea took off in several directions following the Bronte sisters into Romance, or following Edgar Allan Poe into the horror story. A good case can even be made that detective and mystery fiction are a subspecies of the Gothic. Fairy stories like those of George MacDonald bear heavy Gothic stamps upon them leading to the likes of The Lord of the Rings in the mid-Twentieth Century.

But the hallmark of the true Gothic idea had to with loss or decay and certainly with dread. And so it seemed that whenever something was already found to be lost to the society of the present the Gothic was near at hand. Thus Southern Gothic fiction was born in America below the Mason-Dixon line after the fall of the old antebellum South. William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor are two exemplars of the style. Their scenes of poverty and twisted souls seeking redemption are the reflection of the Gothic image of loss and dread. And it didn’t hurt to have a South strewn with the fading ruins of pre-war mansions.

Obviously when we mention Southern Gothic we are now already firmly inside the doorway of that larger category and the subject of this set of essays: American Gothic. But what is it really? What do we mean by saying that Wise Blood is classic example of American Gothic Fiction? Or that the music of David Eugene Edwards is crucial to an understanding of American Gothic Music? Or to say that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a sine qua non of contemporary American Gothic cinema?

Maybe it might be easiest to point to examples of what is and isn’t American Gothic. Edgar Allan Poe’s work both is and isn’t American Gothic. When it relates to the classic European Gothic, as in The Fall of the House of Usher, it isn’t. But oddly enough a story like The Gold Bug, which is not a horror story at all, bears many of the hallmarks of an American Gothic work. This has to do with the use of American settings and feeling of southern vegetative overgrowth.

In other words just because a person is a Goth in America doesn’t mean they have any traces of the American Gothic outlook. (They could indeed be seen in opposition.) Most people who would identify themselves as Goths have their eyes more firmly facing Europe. Much of the original Goth imagery from the early 80’s had a Euro-centric notion of darkness. Interestingly enough, the first rock band of any sort to have Gothic aspects came from sunny Southern California: The Doors. And yet their music references Bertolt Brecht and French symbolist poets.

Or take that great American genre: the Western. Most Westerns are not American Gothics. Stagecoach, with John Wayne, certainly isn’t. Nay, likewise, to your average Saturday matinée oater from the 40’s or 50’s. Yet Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven most certainly is. Why? Many classic Westerns look forward to a time when law and order will prevail and the West will be settled. Unforgiven does not. It looks back at the West as a dark epoch. And that darkness still consumes us. Yet a film like William S. Harts 1916 Hell’s Hinges reeks of American Gothic. Its images portray a lost and morally bankrupt world that is decaying from within. This would be considered a subspecies: Western Gothic.

This puts the bleaker Western in line with the works of Cormac McCarthy, whose fiction is often American Gothic in the deepest sense. Blood Meridian is American Gothic pure and not so simple. And even his contemporary works like No Country For Old Men bear the same stamp. And so does The Road, although set in the future; a future that looks back to the present in mournful terms.

One really sees this in the film version of The Road, which is the most American Gothic post-apocalyptic film ever made. Its vision of cannibal Americans is a dead serious descendant of the EC Comics tradition of the 1950’s. The scene of armed cannibals attired in soiled ragged work clothes and trucker’s caps emerging from a tunnel flanking the dingiest of massive flatbed trucks in a dire autumnal landscape conjures up a vision of an America possibly being birthed today.

In music we return to the Doors. While good chunks their philosophy sources from Europe nevertheless a nightmarish epic like The End taps deeply into the American Gothic with it’s weird scenes inside the goldmine and the ominous blue bus, an allusion to that most American of institutions the Greyhound bus. The 1967 song practically predicts the rise of Manson styled serial killer cult leaders, also prime American Gothic territory. And it is no surprise that Apocalypse Now featured The End as the psychic breaking point of a US soldier all the while hijacking American Gothic imagery into our foreign wars.

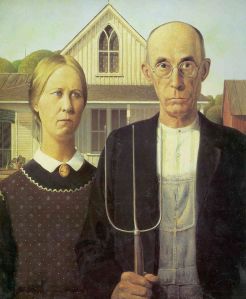

And so what is American Gothic? Look it up and the first thing you will probably come across is Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” painting, which hardly seems to be Gothic at all. Next you might find a dictionary definition based upon that painting: some wheeze about frugality, hard work, socially conservative and rural America.

And yet it is clear that American Gothic as a point of view is a markedly different creature. A sensibility which can include Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy, Nick Cave, Tom Waits, EC Comics, Bernie Wrightson, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Night of the Hunter and Winter’s Bone cannot be reduced to a satirical painting and its comment on old time farmers.

So the elements seem to be simple. First, it is American. That seems rather obvious but in fact it is not. Baseball for instance while wholly American rarely shows up in a Gothic form. Why? It is still quite active. It still has a future. Westward expansion, the post-Civil War South, New England whalers, etc. do not. So it is an America in the minor key, without any sentimental nostalgia.

Second, it must have elements of Gothic decay. And let’s distinguish Gothic decay from other forms decay. Rotting garbage is not Gothic decay, whereas a rotting garbage dump on the Blackfeet Indian reservation puts us firmly within Gothic territory. The decay that has haunted Gothicism all along has been an autumnal specter of the once meaningful, now rendered irretrievably lost.

Third, it must have elements of dread. And this dread is not just fear, terror or horror. It is something still and heavy even when, as in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, it is accompanied by a ferocious engine steaming down the tracks. What makes a horror film like TCM Gothic is not the plot, but the atmosphere.

Lastly, in the best cases, it can have an aspect of sorrow leading to the deeper questions of redemption. Unless it is of the humorous species, which is another tale altogether…

Interestingly the American Gothic arts and world view are NOT postmodern nor even modern. The references they make are filled with bitter ironies. Even in the humorous vein, they tend toward gallows humor rather than pomo media appropriation. The bone furniture in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is not a deconstruction of Ikea. It is like the skull found in the tree in Poe’s The Gold Bug or the iconic buffalo carcasses in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, an emblem much darker, yet symbolically richer, within the American Dream/Nightmare.

And to get an ax handle on that we’ll have to cross the withered plains of American Gothic cinema, music, literature and art.

(Stick around. Part two in this American Gothic series is on its way.)

Byrne Power

Haines, Alaska

5/2/11

As stark as it was, I thought “Winters Bone” was hopeful or at least redemptive in its ending and in its characterizations. Ree had integrity of purpose, and even her weird crank head brother in law and the women who took her to where her father was, seemed like real people to me. Unlike anyone in Flannery O’Connor’s stories all of whom are one sided weirdos … (can you tell I’m not crazy about her stories? ) Yup she’s brilliant, she sees something in the Southern character, but she seems bitter, or, I don’t know, maybe her unilateral darkness stems partly from that judgmental negativity that was so prevalent in the pre-Vatican II Roman Catholic church.

May 19, 2011 at 1:16 PM

Thanks for adding your comment Sara. I think it maybe that Winter’s Bone has an almost fairy tale quality to it. Flannery O’Connor’s work isn’t meant to be strict realism. But then again American Gothic works rarely are. They hover somewhere between a heightened reality and fantasy, which is why the folk tale type elements really work in Winter’s Bone. Even the title has that folk tale quality to it. I think O’Connor’s work also speaks of redemption, but in different terms. I see in her portrayal of freakish denizens of the South a compassionate eye, even through the darkness. I think the degraded characters are a Southern/American Gothic hallmark. Faulkner once was called a “propagandist of degradation”. It’s certainly not for everyone. But I do believe it is worth thinking about.

May 19, 2011 at 1:43 PM

Enter the world of real American Gothic (with a Noir veneer): _Noir_ by K W Jeter.

October 1, 2014 at 8:45 PM

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs by the Coen Brothers seems like it might be American Gothic.

May 9, 2019 at 6:35 PM

Thanks Felicia. Yes indeed it is, and a darkly humorous story at that. The Coen Brothers have often traveled through American Gothic territory, with No Country For Old Men and Fargo being their AG masterpieces. In fact the more I think about it, the more I have trouble thinking of a film of theirs that isn’t on some level America Gothic. See my American Gothic Film Addendum.

May 9, 2019 at 8:36 PM